Promoting public awareness and dialogue about China’s vast air pollution problem is important. Recent research shows that the country is suffering many premature deaths as a result of pollutants from cars, industry, and construction. However a large portion of China’s huge population lacks awareness of the health risks and prevention measures. In recent years there have been some notable campaigns to inform the populace. These include: government ones, such as limits to fireworks at Chinese New Year; societal online debate around the recent “APEC Blue”; civil society initiated campaigns such as Green Beagle‘s citizen air quality monitoring and IPE’s Green Choice Alliance; and informative viral videos such as the “Smog Journeys” video recently released by Greenpeace Asia.

Now, a new documentary about China’s air pollution problem has gone viral. It was independently funded and produced by Chai Jing, a well-known former CCTV journalist who worked at the state media broadcaster for a decade.In 2013 Chai gave birth to a daughter who was diagnosed with a tumour. She announced to the public last year that she would be leaving CCTV to care for her child and to research the reasons for her unhealthy start to life. The resulting 103 minute long documentary is called “穹顶之下” (Under the Dome ((It’s name is borrowed from the Stephen King novel and related TV series, with the “dome” being a metaphor for smog cover.)) ) and was first screened in Beijing on 27th February, before being made publicly available (and free) online the next day. Chai hoped that it would help people answer three questions: “what is smog? Where does it come from? And what can we do about it?” (雾霾是什么?从哪儿来?我们该怎么办?).

“This is a personal grudge between me and smog”

In the space of just two days Under the Dome has been viewed by tens of millions of people in China. Its success raises some interesting questions about awareness campaigns in China. Firstly, it’s clear that the documentary has mobilized some powerful technological tools. It has high production values – no doubt benefitting from Chai’s media experience – and a winning TED Talk-style combination of lecture, live demonstration, and data visualization. It was released online and free, and went viral very quickly on China’s gigantic, sophisticated, and increasingly integrated social media network. Secondly the documentary demonstrates the importance of impartiality in today’s China. Chai chose to fund her documentary personally, independent of government or business. She makes it clear that she is producing it not as a journalist, but as: 1) an individual, saying she has a “this is a personal grudge between me and smog” (“这是我和雾霾之间的私人恩怨”), 2) an ordinary person (“普通人”), and 3) a concerned mother. In the documentary she wears casual clothing and highlights her own previous naivety, acknowledging that she didn’t wear a mask while she was pregnant. She says that while filming she “saw smog through my daughter’s eyes” and was made afraid that her daughter would one day ask “What is blue sky?” (“什么是蓝天”) and “Why do I always have to stay at home?” (“为什么老把我关在家里”). In taking this approach Chai is highlighting the power of the individual citizen in today’s China, with it’s high profile anti-corruption drives, and it’s increasing mistrust of corporations.

The success of the documentary also demonstrates the importance of having an authoritative voice and a strong logical argument. Despite suffering public criticism recently for choosing to give birth to her baby in the US, Chai’s work is well known and generally respected. She was praised for her reporting on the SARS outbreak when she stood on the frontline wearing protective clothing, and for her reporting on the Wenchuan earthquake, when she lived among disaster victims. She is also known for her environmental work, winning environmental awards and producing popular documentaries about her home province’s (Shanxi) severe air pollution problems. In Under the Dome Chai also cites data from numerous authoritative sources. She talks to professors at Beijing University about pollution measurements and to professors at the University of California about the impacts of air pollution on child health. She cites articles, such as one published in the Lancet written by former Health Minister Chen Zhu with other experts, that states that 350,000-500,000 premature deaths result from air pollution each year in China.

The documentary also shows how crucial it is to approach problems constructively in China. Although Chai is cautiously critical of governance issues, the enforcement of environmental regulations, and the dominance of the oil industry, she also depicts solutions, visiting historically smog-ridden places and analysing the measures they have employed to overcome the problem. In London she pays her respects at the graves of those who died during the city’s Great Smog and looks at how the local government reduced air pollution by 80% in 20 years. In South Wales she visits a closed down coal mine, talking to officials about the way the UK has switched from coal to oil and gas. In Los Angeles she notes how reliant the city is on cars and watches LA city officials handing out tickets to those drivers who have not retrofitted their heavy diesel vehicles with air filters.

Calls for public participation

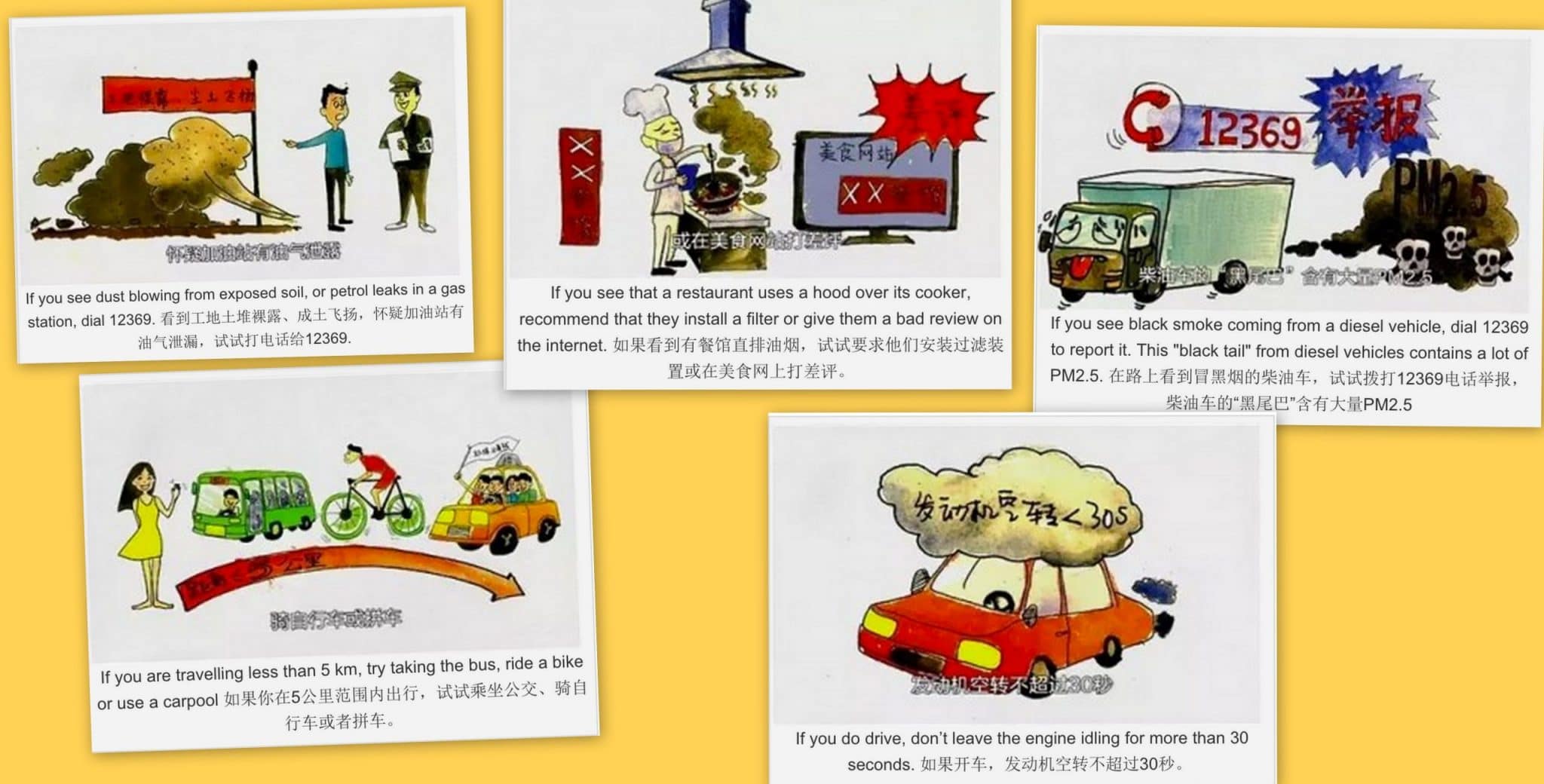

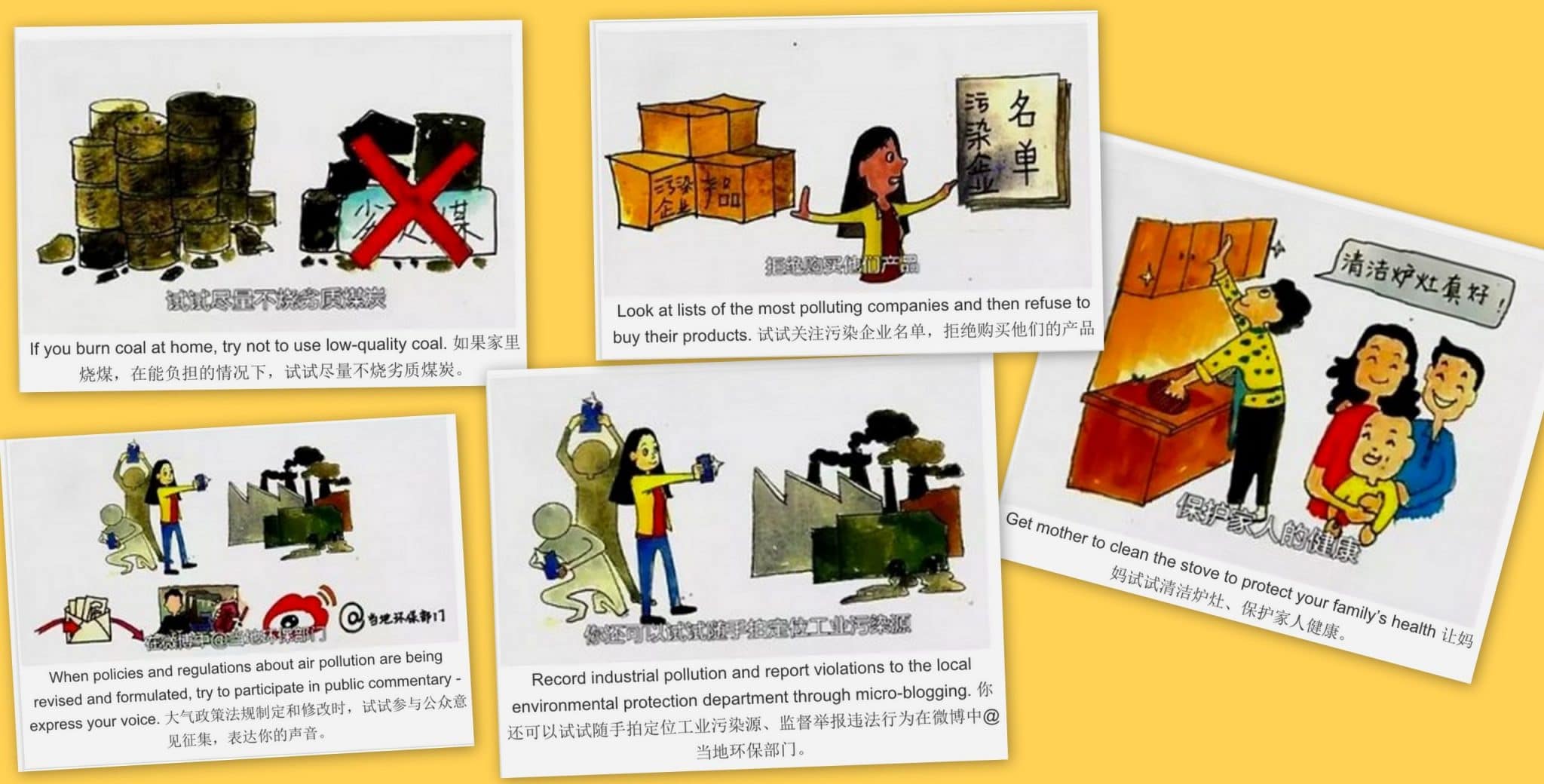

The documentary also contains interesting commentary on public participation in the fight against China’s air pollution problems. Chai Jing talks about projects run by IPE (The Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs), a Beijing NGO founded by the prominent environmental journalist Ma Jun, mentioning their extremely effective citizen-science pollution mapping work. The documentary also features a one-minute long cartoon titled: “I can do something to fight the smog” (对抗雾霾,我为空气做点事, see below for screenshots and captions). It was produced by another Beijing environmental organisation Friends of Nature, one of China’s oldest NGOs. The inclusion of IPE and Friends of Nature in such a widely watched documentary is a positive step for China’s environmental NGOs. The day after it was made available online both IPE and Friends of Nature released messages saying that there websites were down due to high traffic and receiving an unprecedented number of messages and visitors.

The success of Under the Dome is also an interesting example of collaboration between society, NGOs, media, academia, and government. One article in the Chinese media reported that “it’s a public policy inquiry, its an example of public participation” (是一次公共政策的质询,更是一番公众参与的行动). In the documentary Chai herself repeatedly calls for greater public participation, asking what individuals can do. At the end of the documentary she implores everyone to address these issues starting with their own lives (从我做起). She encourages people to get involved with environmental organisations or just do what they can, saying: “for ordinary people like us, if you do not have time to participate in an environmental organization, then you can do what we did with Friends of Nature and make a small animation” (像我们这样的普通人,如果你没有时间参加一家环保组织,那么你还可以做什么?我们和自然之友合作,做了一个小的动画). She also gives an example of calling a hotline number (12369) to report a construction site that fails to take anti-dust measures outside of her apartment. She says that “if you do not call then the number 12369 is just a number” (如果你不打,12369就只是一个数字).

China’s Silent Spring?

How significant is Under the Dome? It is certainly not perfect. It does not delve deep enough into the solutions presented and their possible impact on China’s economic development. Some of the comparisons that Chai Jing makes with Western countries lack relevance because the socio-economic-political contexts are too dissimilar. Chai also does not adequately address some policy and social issues – gender issues for one being notably absent in the Friends of Nature’s cartoon (which talks about “mother in the kitchen”, see below). In a Weixin post titled “What Under the Dome Did and Didn’t Say” (穹顶之下说了什么和没说什么), Guo Peiyuan of SynTao, a Beijing-based CSR and sustainable investment consultancy company, also noted other issues that Chai Jing did not address. Guo says that Chai largely ignores the pressure of GDP expectations on local government, saying that local government performance is so tied to GDP growth that is a disincentive for the enforcement of environmental regulations. Guo also says that Chai fails to mention the Green Supply Chain or talk about Green Finance. Other critics also wrote about how the success of the documentary demonstrates the failure of liberal media and the rise of the celebrity in China, noting how it would have been much less successful if Chai had not used the prestige and social connections accumulated during her work in state media.

However, despite these shortfalls, if the documentary raises awareness and sparks debate then that is surely a good thing. After already being viewed by over 60 million people, Guo Peiyuan said that “Under the Dome is perhaps the Chinese version of Silent Spring, because it presses on the public’s pain, and has caused a large middle-class discussion of environmental issues” (《穹顶之下》可能就是中国版的《寂静的春天》,因为它戳到了公众的痛处,引起了中产阶级对环境问题的大讨论). This is not the first time that this has happened in China. In recent years other significant events such as extremely high levels of air pollution during Beijing’s “Airpocalypse” in 2013, the release of government action plans on air pollution, and the air quality monitoring campaign of 2011, have all been labelled “Silent Springs.” ((Silent Spring is an environmental book published in 1962 that is cited as a great catalyst for the environmental protection movement in the West.)) Certainly Under the Dome has got an unprecedented number of people, across a more diverse section of society, talking about air pollution. Crucially perhaps, the documentary has been endorsed by the newly appointed Environmental Protection Minister Chen Jining and is sponsored by state-run media. With the 2015 National People’s Congress set to be held this week, it should initiate some political momentum. In the Chinese context that is significant.

The Friends of Nature cartoon

See here for full cartoon, below are screenshots with captions translated by CDB: