This article was originally published by 公益资本论. This is an abridged translation.

If a party or government cadre from the 70s travelled to the 21st century, and they were able to see today’s philanthropic sector in China, perhaps they would pronounce the same phrase uttered by the old party cadre who visited the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone in the early 90s and couldn’t believe his eyes – ‘we strove so hard for years, just to go back to pre-revolutionary times overnight’.

People in those days had a completely different frame of reference. The main attitudes of the time were: “capitalist philanthropy is hypocritical”, “philanthropy is something that governments should deal with, and only when governments are unable to deal with it do philanthropists appear” and “the increasing popularity of philanthropy is not a good thing because it means the inequality gap is widening”.

For a long time, the People’s Republic of China was wary of capitalism and private business. The government monopolized all public sectors including education, health and social welfare. Non-government subjects were not only forbidden to engage in philanthropic activities, but were also seen as criminals if they did.

Yet, there were always vulnerable groups that needed help. What could be done to address their needs? The solution at the time was that the government oversaw all kinds of work related to poverty-alleviation, and they tried to make sure that every citizen was fed, and every child received an education.

Such practices persisted for years until the 80s, when China’s financial capabilities could no longer support them.

The turning point came in December 1978, when China held the Third Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, marking the beginning of the Reform and Opening-up Policy. The shift in macro-politics helped to prompt the birth of several philanthropic organizations.

July, 1981 – The China Children and Teenagers’ Fund is created. It is the first philanthropic organization with its own legal qualifications in China.

1984 -1985 – Led by high-level officials, the China Foundation for Disabled Persons and the China Green Foundation are founded.

In the early years, all philanthropic organizations were founded and led by the government, and were therefore often referred to as GONGOs (government organized non-governmental organization). Similar to state-owned enterprises, the organizations enjoyed all kinds of favorable policies, and staff members were all civil servants. Charities founded during this period are scarce in number. Since everyone was new to philanthropy, fledgling organizations at the time grew very slowly.

Starting in September 1988, the State Council passed the Management on Foundations, stipulating the nature of philanthropic foundations, conditions of establishment, financing, use of funds and management. From then on, modern philanthropy began to take root in mainland China.

December, 1988 – the China Women’s Development Foundation is created.

March, 1989 – the China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation and the China Youth Development Foundation (CYDF) are created. The latter started the renowned Hope Project.

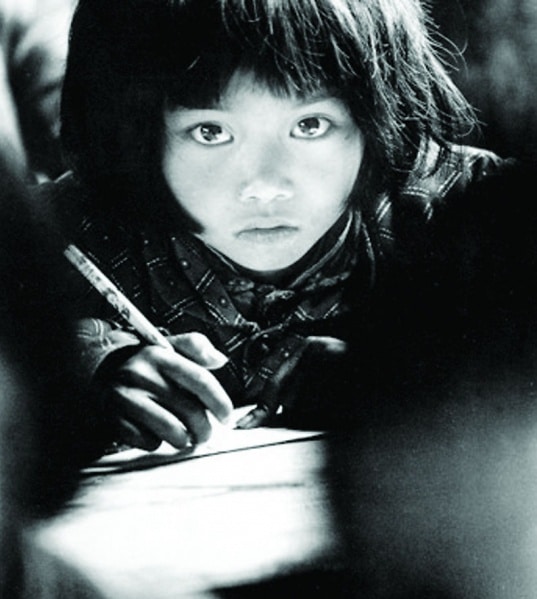

“Our country was very poor back then. Many children were unable to afford their tuition fees, and each year there were one million children who discontinued their studies. Since government funds were limited, each teacher in rural schools was only allowed one piece of chalk”, says Xu Yongguang, initiator of the Hope Project, a milestone public welfare project in China’s charity history. He also served as the secretary-in-general of CYDF during that time.

Government-organized public-fundraising foundations represented by the CYDF made great contributions towards helping the vulnerable. They were also the product of monopoly and bureaucratization. As reputed scholar Zi Zhongyu puts it: “they were an abnormal kind of organization that came up during the transition period.” With increased demand in the philanthropic sector, “they became an obstacle for the development of private philanthropy.”

Hope Project’s famous “Big Eyes” girl Su Mingjuan

Photo Credit to Xie Hailong

Economic reform during the 90s created a lot of momentum, but it was not until June 1999 that the ninth National People’s Congress passed the Charitable Donation Law of the People’s Republic of China(《中华人民共和国公益事业捐赠法》)as the first law of its kind.

In the same year He Daofeng, the entrepreneur who previously worked at the State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development (CPAD), returned to CPAD and took charge of the China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation (CFPA). During his time as head of the foundation, he launched a marketization reform, refusing government subsidies and trying to manage CFPA as an enterprise in which staff were no longer civil servants.

After around ten years, CFPA had become one of the best philanthropic foundations in China — or even the best, as many believe. Even now, there has not yet appeared another GONGO like CFPA. The foundation became a crane standing among chickens. As Tsinghua University Professor Deng Guosheng puts it, “CFPA’s reform carried the obvious signs of one-man heroics, and can’t really be considered representative.”

It was always difficult to implement government reform, not unlike the twists and turns of state enterprise reform. Philanthropic development had to wait for the power of civil society to manifest itself.

As the world walked into the 21st century, China introduced its first regulations which aimed to encourage the development of non-public fundraising foundations. The Administrative Regulations on Foundations is believed to have been an ice-breaking document for non-governmental charities.

December, 2014 – The Ai You Foundation, formerly known as the Huaxia Foundation, becomes the first registered (regional-level) private foundation in China.

June, 2005 – China’s first national-level non-public placement foundation, the Heungkong Charitable Foundation, is created.

Also in 2005, the annual government work report first spoke of “supporting the cause of charity”. This should have boosted the development of the charity sector. However some regional governments added the words “as a second source of tax revenue” and started to forcefully apportion gains and seek donations, so that charity was instead tainted by power and capital.

Long-standing abuse of power was first exposed during the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake. The earthquake, the first national disaster to incite widespread citizen participation, ignited people’s enthusiasm and donations. As there were no credible and accredited private foundations, more than 80% of the 76 billion yuan in donations went to government accounts. Though it is believed that the government didn’t misappropriate the money, a lack of transparency and accounting confusion made many donors discontented with the government-dominated donation system of the time.

The public’s discontent with the donation system can be properly illustrated with the example of Jia Duobao. The herbal tea company donated one hundred million yuan to earthquake victims in Wenchuan. Later the company made an inquiry into their donation, but the foundation that received the money was unable to explain its whereabouts, which made the donors quite unhappy. Then in 2010, when an earthquake struck Yushu in Qinghai province, Central China Television (CCTV) held a fundraising event and stipulated beforehand that all donations must go to the Ministry of Civil Affairs, the Red Cross Society of China and the China Charity Federation. Jia Duobao donated 110 million yuan this time, but insisted the money go to CFPA. Authorities didn’t accept Jia Duobao’s conditions, and as a result, all donations went to the Qinghai Provincial Government.

Today it is still commonly believed that 2008 was the first year of a new era in China’s philanthropy sector, because the Wenchuan earthquake taught millions of Chinese people a lesson in philanthropy. From then on philanthropy became an increasingly hot word, no longer only discussed in academic fields. In addition, Chinese donors also learned how to actively research the destination of their donations instead of passively handing over their money to unknown accounts.

Distrust in government-organized philanthropy peaked in 2011 with the Guo Meimei incident , which aroused public uproar. The domino effect of social media displayed its destructive power in the philanthropy sector for the first time. Chinese charities encountered unprecedented skepticism, but this time the unfriendly voices came not only from the authorities, but also from ordinary people.

For many in the industry, the period between 2011 and 2012 was the hardest time for China’s philanthropy sector. The Red Cross Society of China took a huge blow and many private organizations were asked to present their financial records when raising funds.

Despite an investigation that proved the Red Cross Society of China innocent, people lost trust in GONGOs. As a result, when the Lushan Earthquake occurred in April of 2013, nearly all GONGOs were put into the doghouse. In stark comparison the One Foundation, a private foundation founded by film actor Jet Li, raised 350 million yuan from more than 6 million individual donors.

The rise of the One Foundation and many other private foundations that sprung up at the time was connected to a series of favorable policies in the “post-Guo Meimei era”.

March, 2013 – The Institutional Reform and Transformation of Government Functions (《国务院机构改革和职能转变方案》) is released. The regulation is considered to be a breakthrough for social organizations. One of the highlights is that social organizations including charities are no longer required to first apply for the approval of professional supervisory units, but they can instead register with the Ministry of Civil Affairs directly.

September, 2013 – The State Council publishes Guidelines for Purchasing Social Services from Social Forces

(《关于政府向社会力量购买服务的指导意见》)

November, 2013 – The Decision of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Some Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening the Reform (《中共中央关于全面深化改革若干重大问题的决定》) is published. The report speaks of “vitalizing social organizations” and “completing a tax-free system of philanthropy”.

Still, the rapid development of the philanthropy sector could not offset the public’s increasing skepticism towards charity. This skepticism was not only aimed at GONGOs, but also at private foundations. 2014 was a year full of controversies.

January – The Smile angel Foundation is accused of affiliate transactions.

April – The One Foundation is criticized for “spending money too slowly”.

March – Orphan Yang Liujin receives donations that are more than abundant (超限募捐), stirring controversy among the public.

Meanwhile a degree of civic participation, long anticipated, also began to show itself, best represented by the popularity of the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge. Like in the United States, the Ice Bucket Challenge was quite popular for a time. Many foundations took the chance to raise money and received unprecedented support. For the first time, people were convinced that large-scale public participation in philanthropy could happen in China as in western countries. Encouraged by people’s enthusiastic participation, the Tencent Foundation launched the 99 Philanthropy Day, successfully mobilizing over two million people to donate 230 million yuan in just three days.

At a time when everyone can make their opinion heard and public sentiment can be multiplied by orders of magnitude online, the still fledgling philanthropic sector faces both great opportunities and a grave crisis. At this time the Charity Law, after a long period of lobbying and preparation, went into effect in China.

March, 2016. The 12th National People’s Congress passes the Charity Law. This way charity organizations of all stripes, which have been developing in a disorderly fashion for over 30 years, finally have a law that covers them.

The Law was acclaimed by many in the sector, including Xu Yongguang, deputy president of CYDF, who sees it as a way to restrict the government from interfering in the fundraising process, sanctioning any form of apportioning donations that does not respect the rights of the public. This will rely, however, on every citizen and organization making use of the Charity Law to protect their rights.

Further reading:

From Wenchuan to Lushan: An Overview of Disaster Relief NGO Efforts

Xu Yongguang: the “ALS Ice Bucket Challenge” in China is not “unpleasant”

What is the New Pattern and New Vision for Chinese Charity in 2016?