There is, of course, more than one way to think about philanthropy. What follows is, therefore, a personal view, and it differs a good deal from views that are widely held these days. It derives from my experience of having been “on both sides of the table”: five years as president of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and six years as president of the University of Chicago. Others, depending on aims and experience, will have very good reasons to hold a different view. I only wish to offer some aid and comfort to those made slightly uncomfortable by the currently dominant discourse.

Both philanthropy and higher education are subject to fashion, much of which comes in waves from the world of business. This is understandable because trustees of both kinds of institutions often come from the world of business and suppose quite naturally that the application of current business practices to philanthropies and institutions of higher education would cure their many ills. By this I do not mean to suggest that philanthropies and institutions of higher education are not businesses. They certainly are. But it is essential to understand what kinds of businesses these are. For a start, the underlying logic of for-profit businesses and not-for-profit businesses is inherently very different, and much else flows from this quite naturally. This might at a minimum call for more modesty when pointing the finger across the boundary between the two.

If one doubts that business is subject to fashion (one might even dare to say mere fashion), one has only to look at one’s shelf of business books accumulated over a few decades. One might similarly review the qualifications and management styles of the leading CEOs of the last few decades. Most of these books have very short intellectual shelf lives for all of their momentary popularity. Yet they often come cloaked in a kind of moral superiority suggesting that one is both incompetent and morally bankrupt if one does not subscribe wholly to the view being advanced. The waves of “total quality management” and “continuous improvement” were good examples. They were not devoid of valuable insights. But they were preached and promoted by armies of consultants in ways often reminiscent of old-time religion and its revival meetings—you must hold hands with the person on either side of you and believe, and if you don’t there is the clear likelihood that you will go straight to Hell. “Strategic planning” has proved more durable but has had some of the same features. Every business, whether for-profit or not-for-profit, must plan for how it will carry on its affairs over a certain time horizon. The problem with many strategic plans, especially in the for-profit world, is that the time horizon is not nearly long enough. But in the worst of cases, it can lead one to reduce complex matters to slogans, which, once adopted, can blind one to the continuously shifting landscape if not the actual earthquake going on around one.

Some of the currently fashionable words having a particular effect on philanthropy are “impact,” “assessment,” “entrepreneurship,” “venture.” They will be found in the course and reading lists of every business school and on the websites of a good many foundations. It is not that these terms are meaningless. But they have much to do with the ways in which enormous wealth has been created by some individuals who then (blessings upon them) wish to become philanthropists. They have solved one very concrete problem—how to make a lot of money in some particular line of business—and they suppose that life consists for the most part of similar kinds problems that are amenable to similar kinds of solutions. Most of the world’s truly serious problems, however, are very much harder. The philanthropist who limits his or her field of vision to problems even of the dimensions of how to take a company from startup in a garage to a market capitalization of many billions will misjudge the nature of many of the world’s problems and simply ignore a good many others. Finally, it must be said that a great deal of wealth has been creating by standing in the right place at the right time, or having genuinely incompetent competition, or benefitting from inappropriate power and influence. A genuine philanthropist does not get to accomplish things by any of these methods, for the enemies to be overcome ultimately reduce themselves to suffering and ignorance, which are implacable and implacably complex.

The philanthropist may, of course, choose to solve a problem that is well defined and demonstrably solvable. One can reduce the number of children’s deaths from malaria in the developing world by distributing mosquito netting at a quite low unit cost. It will be possible to count the number of nets and their costs and reasonably estimate the number of lives saved. Who could not want to see such a thing happen? Suffering will have been reduced. But what about the ignorance in which these children may live out their lives even if they are healthy? That is a much more difficult problem that afflicts the developed world every bit much as the developing one. And if we care about the human spirit and enabling human beings around the globe to live the fullest possible lives, we must not ignore it just because we find it difficult to measure the dimensions of either the problem or its solution.

Philanthropy is not a branch of the social sciences, though it may attempt to ameliorate social ills. The philanthropist must understand that not everything is easily measurable and that the correlations of the social scientist do not necessarily lead unproblematically to effective policy. And one would be bound to admit that the social sciences have been notoriously poor at predicting even major catastrophes. Some of there predictions can turn out to be simply wrong. Hence, one cannot always approach philanthropy as if it were a controlled experiment in which one could feed one group of mice a lot and another group a little and then discover which group got fat. John Maynard Keynes, a great social scientist by any measure, put the matter extraordinarily well when he wrote the following: “the statement that Queen Victoria was a better queen but not a happier woman than Queen Elizabeth” is “a proposition not without meaning and not without interest, but unsuitable as material for the differential calculus.” The philanthropist must always bear in mind that many of the most important things in human life are not suitable material for the differential calculus.

American culture sometimes contributes to the failure to take this into account. There is no doubt that the United States has a culture of generous philanthropy that exists nowhere else in the world at anything like the same level. That generosity has created and sustained the world’s greatest universities, conquered terrible diseases, and much else. But there is a strongly practical, sometimes shortsighted, and ultimately anti-intellectual streak in this culture as well. This society has often felt compelled to justify major undertakings in terms of their contribution to the Gross Domestic Product or the national defense. But we have by now learned very well that GDP can grow while leaving behind an unconscionable number of poor. And defense spending can grow without any view to what might make the nation most worth defending.

The culture of sports also can have unfortunate effects. The public likes to know who wins and who is ranked number one or in the top ten or top 100. This appetite for rankings can produce utterly perverse effects in some areas of endeavor in which philanthropy is important. Higher education may be the most egregious. Many philanthropic dollars have been unwisely spent in the effort to make one or another college or university “more competitive” and thus higher in the rankings of such institutions. It is nonsense to suggest that one could construct a meaningful ranking in the first place. But the criteria according to which institutions rise or fall in such rankings as those of U. S. News & World Report have essentially nothing to do with the quality of educational experience that any particular individual is likely to have in any particular institution. For example, the fact that one institution has rejected many more applicants than another guarantees nothing about the experience of the student who enrolls at the one or the other. The fact that one institution is very much wealthier than another and thus is able to spend much more per student than another guarantees nothing in and of itself about whether that wealth is being invested wisely in things that might contribute to a better education. Often the philanthropic dollars that produce the wealth of institutions are invested in ways that pander to the rampant consumerism of our society in general and of very many eighteen-year-olds in particular.

Worst of all is the money spent on intercollegiate athletics. It is sometimes claimed that successful athletic teams generate philanthropy for other purposes. This has been shown not to be true in the main. Yet a good deal of philanthropy in higher education goes to supporting athletics programs in which students of lesser academic ability are segregated from the intellectual life of their institutions and in the worst of cases graduate at very much lower rates than their fellow students. Participation in athletics can be a valuable part of an undergraduate education, just as playing in the college orchestra or acting in a play can. But the goal cannot be allowed to become rising to number N from number N-x simply for its own sake.

Philanthropy must in the end be about values worthy of the name. These are not easily measurable or rankable. And they may not be novel or change much over time. It may not be possible to realize them easily. But failure in the attempt does not necessarily make the attempt unworthwhile. This argues for a philanthropy that resists fashion and the pursuit of novelty for its own sake. The worst thing about much philanthropy in the foundation world especially is that it is fickle.

It is well then to begin by asking not what is the problem to be solved, but what is the phenomenon to be addressed and what are the values to be realized. The answer to this question must predominate over whether the outcome has impact that is easily measured or can be easily assessed. This may entail a willingness to live with ambiguity and what might be thought to be failure in more conventional terms. The fear of failure can stand in the way of noble undertakings. Even more important in this context, however, is that one need not be deterred by a fear that one may never know whether one has succeeded or failed except that one has valued and supported some activity. There is a cost/benefit analysis that is usefully undertaken in this context as well. Efforts at impact and assessment may simply cost too much as a fraction of the total resources being expended. All of us surely believe that certain activities are inherently worthwhile and deserve support even if they cannot be shown to cure ills that might be measured by the tools of social science.

This raises an ethical question. Some problems can be solved and some social ills measurably ameliorated. Given the enormity of the social ills afflicting even the richest country the world has ever known, to say nothing of the developing world, how can one devote resources to activities that do not ameliorate these ills or that may even disproportionately benefit those who must be seen to be privileged by any reasonable definition?

The logical extreme of the position implied by this question, given that the world’s social ills will almost certainly never be entirely cured, would hold that no philanthropic resources whatever should be devoted higher education and cultural institutions except perhaps to the extent that higher education trains people who will work directly on social problems. Such a view surely implies similar constraints on consumption by the well-to-do. How can one devote one’s personal resources to anything other than basic necessities in the face of human misery? This points directly to the question of income inequality and income redistribution. Individuals will have widely varying views of this, but nations will arrive at compromises among these individual views and engage in more or less income redistribution for social and other purposes. But every nation—including the most socialist in the world today—and every individual could always do more.

A better approach to the ethical question would start with some attempt to describe the rights of all people, rich and poor alike. Martha Nussbaum describes this (somewhat more expansively than Amartya Sen) in terms of capabilities that every human being is entitled to realize. These capabilities include, of course, good health and nutrition, education, and political freedom. But they also include the capability of thought and imagination and creative work. Seeing the realization of this capability as a fundamental right provides the framework in which we can advocate the investment of philanthropic resources in cultural institutions and in those aspects of higher education that serve more than a merely instrumental purpose. Although it will not be easy to strike the balance among capabilities in the face of resource constraints, to fail to invest in the realization, on the part of as many people as possible, of the capability of what we might call the life of the mind and its creative potential is to deprive at least some number of people of a fundamental human right.

Understood in this way, the humanities and the arts are essential to being fully human and are far from being mere entertainment. This is not to say that everyone participating in the arts by attending plays and concerts is deeply engaged in living the life of the mind. And it does not prevent one from regarding some artistic creation as trash. But simply to arrive at such a critical judgment is itself to exercise the imagination in a way that society should value and promote. In this way, the cultivation of the humanities and arts can be understood to be one of the responsibilities of a society to its people and an essential part of becoming fully human for the individual.

It will be very hard either to prove this or measure it. How would we know that more people are living the life of the mind? Taking college courses in the humanities, attending concerts and plays, and visiting museums do not in and of themselves guarantee it. We are forced to console ourselves with the belief that doing these things is better than not doing them and that promoting them is a worthy undertaking.

These activities turn out to be expensive, and this returns us to the question of income redistribution. Absent some commitment on the part of society at large and philanthropy in particular, they will become increasingly the province of the rich. This is a fundamental injustice in the terms I have outlined. The embarrassing fact, however, is that many in the United States at the moment seem fully prepared to deny to a substantial fraction of the population the capability of good health and adequate food and shelter. It should perhaps not be surprising then that these same people are fully prepared to withdraw public support for the humanities and the arts. This leaves the responsibility for the necessary redistribution of income to individual educational and cultural institutions. Each must enable access for the less well-to-do by requesting or simply requiring the more well-to-do to contribute a greater-than-average share of the costs. Philanthropy plays a very big role in this, a role that is favored by the tax code. But placing this responsibility ultimately on thousands of individual educational and cultural organizations is at a minimum a very inefficient method for achieving a result that is crucial to the well-being of the society at large.

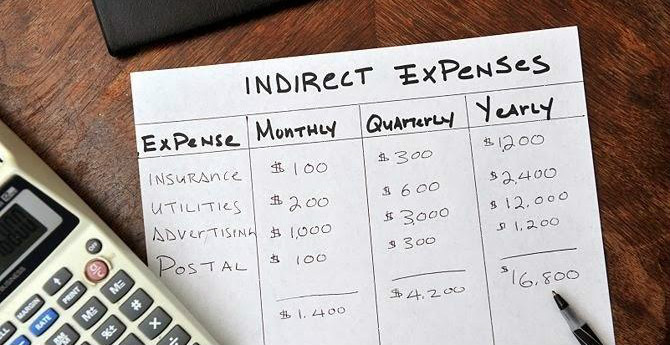

Accepting the appropriateness of philanthropic support for the humanities and the arts, how might one think about actually providing it? A foundation that would have this as its principal goal must begin by understanding thoroughly that it only supports money-losing businesses. If educational and cultural institutions of the kind we have in mind were not by their nature money-losing businesses they would have no need of philanthropy. Market forces have shown clearly that they will not provide the necessary support for such activities.

This is perhaps the hardest thing for some philanthropists and trustees of philanthropies to understand, coming as they sometimes do from the world of for-profit entrepreneurship. Some will say that they do not wish to make donations for the sake of covering deficits. But every philanthropic dollar goes to cover a deficit. The only question is how large a deficit is the institution reasonably prepared to try to cover. Expenses and revenues must of course be brought into balance, and this requires careful planning and estimates of risk (as in any for-profit business). But there is no such thing as saying that the first dollar donated during the fiscal year is not covering a deficit whereas the last one is. Similarly, to say, for example, that an institution ought to live within the means provided by its endowment without reducing its real value is only to say that the institution’s deficit should be covered by past donors who created the endowment rather than by present donors.

Another feature of activities such as the humanities and the arts that does not respond well to the culture of the for-profit world as we encounter it today is that they operate on very long time horizons. One might argue that the for-profit world could benefit from operating with longer horizons in view as well. But the pursuit of the humanities and the arts is by its nature timeless and endless. Its methods may change over time, but its goals remain essentially the same, and thus there is no such thing as the quick fix or the quick profit.

This runs headlong into modern’s society’s unquenchable thirst for novelty and its correspondingly atrophied attention span. Setting aside the mass media and their attitude toward what ought to be conveyed as news to the citizenry, even universities can fall prey to the pursuit of novelty for its own sake. This has a way, without malice necessarily, of privileging the sciences and technology over the humanities and the arts. Science is by its nature about the pursuit of the new. Discovery is its goal—sometimes patentable and revenue producing. Thus, the university’s own communications effort may give a much more prominent place to the sciences than to the humanities and the arts because these are often occupied with ancient concerns even if expressed in new forms. And if we care about undergraduate education, we will find it especially difficult to produce good newspaper copy by current standards.

The big news in undergraduate education on every campus every day ought to be that some large number of undergraduates felt the thrill of grappling with an idea new to them, never mind whether that idea was first expressed in Greece in the fifth century B.C.E. or the day before yesterday. This should not be confused with a wish to have them encounter some fixed body of ideas and works embodying them. The goal is to nurture a hunger for ideas ancient and modern, western and non-western, and an enduring regret that one will never have read enough or know enough or have exhausted the mind’s capacity to stretch. Yet no newspaper will make this the lead story day in and day out.

The lesson for the philanthropist is that if one cares about the humanities and the arts, one cannot reasonably insist on novelty as the primary goal. Nor can one insist that the goal be reached in some near term, after which one is at liberty to direct one’s attention elsewhere, perhaps leaving an institution with a financial burden that it may have difficulty sustaining. To promote the humanities and the arts is to promote more than anything a way of life rather than a body of information. As a result, philanthropic supporters of the humanities and the arts must be content to patient and steadfast and not to have their names on the front page of the newspaper very often.

A frequent debate in philanthropy concerns the difference between support for specific programs in an institution and core support for the underlying costs of the institution’s activity. Some foundations are highly allergic to the latter. Here, too, different balances can be struck. But one cannot in good conscience only push institutions to pursue novelty without taking some account of their need to keep the lights on and the reluctance of many donors to help with such mundane needs.

All of this is to suggest that there are extremely valuable and important kinds of philanthropy that do not have novelty as a primary goal and that do not lend themselves to metrics for impact and assessment. Above all, they do not lend themselves to the self-promotion of the philanthropist. They derive from values and belief and commitment, even or especially in the face of forces to the contrary. In the end, it might even be more satisfying to know that one has remained true to one’s values and belief and commitment despite demonstrated failure. The likelier case is that one will never know for certain whether one has succeeded. But the fear of failure and an inability to live with ambiguity are as paralyzing in philanthropy as they are in any other human activity.

How then to go about being a philanthropist? Modesty is a desirable attribute. This brings me back to my experience of having been “on both sides of the table.” I am often asked about the difference. In my own view they have something profound in common. As a university president I always assumed that my job was to listen for other people’s good ideas and then try to find the resources with which to help them realize those ideas. As a foundation president I assume that my job is to listen for other people’s good ideas and then try to provide the resources with which to help them realize those ideas. This of course assumes in the university context that one picks very good people—people with good ideas and a commitment to collaboration for the common good. The president cannot possibly alone have all of the good ideas that it takes to make a great university. Admitting that is crucial to achieving the necessary collaboration. The foundation president cannot possibly have all of the good ideas either and should not assume the right to tell everyone else how they ought to conduct their affairs. Listening is perhaps the greatest skill of them all.

Although the foundation president can choose the right colleagues, the foundation does not choose its grantees in quite the same way. It requires especially careful listening. In the end, as in most other activities in life, it requires figuring out whom one can trust. And given trust, there needs to be some willingness to gamble. When I hear talk of venture philanthropists and entrepreneurial philanthropists, I often think that we are a lot more like bookies. With some ability to read the racing form, we go out to the track, and when we spot a good-looking horse, we decided to put two dollars on the nose of that one. Then we can only stand back and see what happens, knowing that if we don’t lose once in a while we will never win big either.

March 2011